Interview Date: April 30, 2023

Table of Content

CREATOR INTERVIEW

We, as newsletter creators, talk about consistency a lot. But, can you imagine publishing your weekly newsletter consistently for 29 years?!

This is something huge and we need to talk about it. So, today, we have a very special guest who makes the impossible possible.

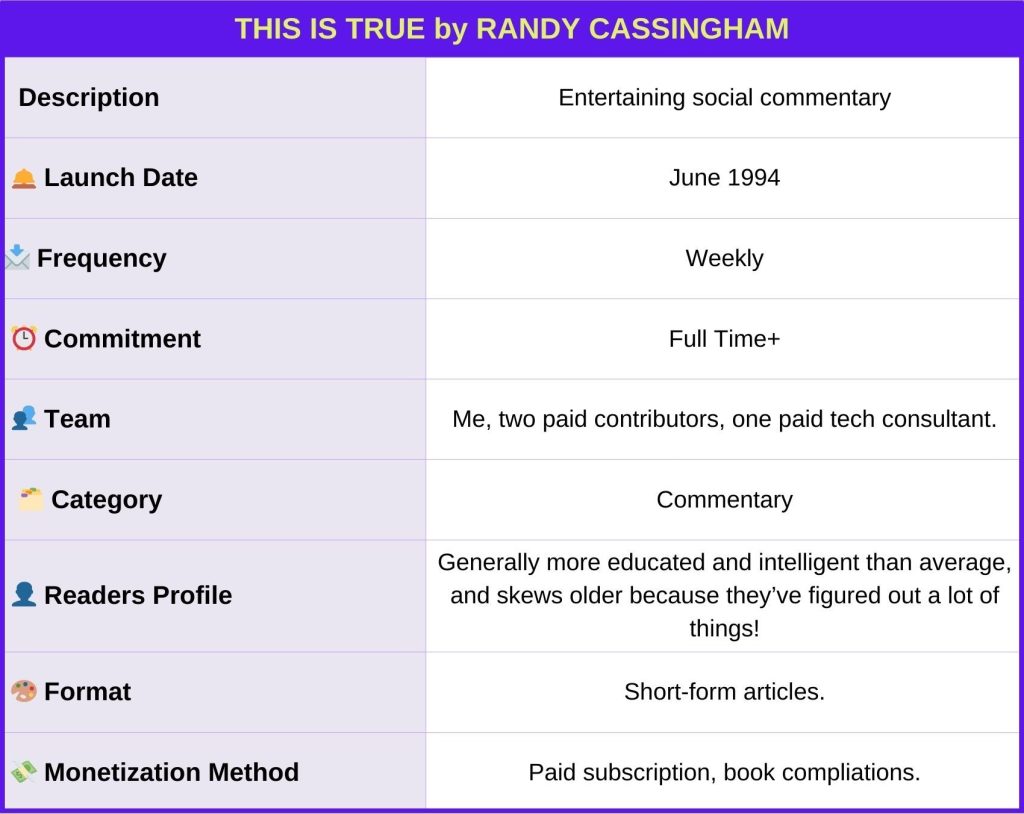

Randy Cassingham is the creator of the oldest entertainment email publication on the Internet, and is still publishing it every week since 1994!

His newsletter, This is True, is an entertaining and thought-provocative news commentary on the human condition.

We talked about how newsletter space has evolved since 90s, what it takes to share more than 1,500+ issues and how he managed to keep himself updated.

As you can guess, this will be longer than other issues. But, is it really long? We tried to pack his 29-years of experience in an interview with 20-minute reading time.

So get your coffee, tighten your seatbelts and enjoy it!

NEWSLETTER IDENTITY CARD

TOOL STACK

- ESP → AWeber for free, custom for paid (into Socket Labs)

- Writing → Wordperfect

- Keyboard → Dvorak layout

- Note-taking → Textpad

- Design → Self-designed in HTML

- Newsletter Building → Custom

- Growth → Publer (social media posting tool)

- Web CMS → WordPress

- Back End → MariaDB (beyond what’s used by WordPress) with custom interface

MEET THE CREATOR

Welcome Randy. Let’s start with getting to know you.

I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was 5 years old, and aimed toward being a newspaper columnist. But when I went to journalism school, I found I couldn’t just be a columnist: I’d have to work my way up from reporter first, and I had no interest in being a news reporter.

I instead took a tech publishing job with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and from that high-tech environment learned about this new thing called the Internet, and I put my columnist idea and the Internet together and realized I could publish myself on the biggest “printing press” ever created: the Internet.

I quit my day job and went to work full time on This is True — which was quite a leap of faith considering it was 1990s!

Along the way I’ve done some side projects such as the True Stella Awards (a newsletter and book about crazy lawsuits), the Get Out of Hell Free card (an offline physical meme that went viral and drove traffic to my online efforts with more than 2 million cards sold), and the Honorary Unsubscribe (an obituary about someone who died recently who was a very interesting person who did good things for humanity, but was probably not well known).

START

What is This is True all about?

At its core, This is True is news commentary and, by extension commentary on the human condition. I use weird news as my vehicle to make it fun to read.

Each week there are 10-14 short stories, each with a pithy “slug” (short title) and a tagline — the commentary, which I bill as humorous, thought-provoking, and/or opinionated. With luck, I can check all three of those boxes.

When you started, the internet had a limited number of benchmarks to help you to build your business model.

How did you figure out how to become successful in online publishing? What was your business model and how did it evolve?

My goal was to make enough to live on, and since I was living pretty well on my NASA salary, that was my benchmark. I knew it would take a while to get to that level, so I didn’t quit NASA for two years so my income could ramp up. At that point, I moved from California to Colorado to make it much harder to give up and go back to NASA.

Also, I had saved up enough money to live on for two years even if things didn’t work out. At the end of those two years, I still had my savings, so I used it as a down payment to buy a condo.

My main income came from a printed book compilation of the first year of stories and, interestingly, newspapers started buying TRUE (as I call it for short) as a column.

Then the Creators Syndicate, the largest feature syndicate in the newspaper space, offered me a contract. I turned down the offer because I wanted total control and figured that the Internet would really hurt newspapers in the long run, and receiving half of the income from a dwindling customer base wouldn’t be a smart deal.

I self-syndicated to the newspapers who wanted the column, though as newspapers started dying off, that income declined. Book sales continued, and then later I had another idea, which I’m sure we’ll get to.

Most look at benchmarks like open rates and CTR. Yes, there’s something to be learned from those, but they’re absolutely not the key. Money is a crude measure, but if your goal is to make a living, what is more important? Readers vote with their eyeballs, sure, but they support your work with money …or not.

I have literally said to my readers that I’m not making enough and will need to raise my subscription rate. Some quickly lock in their lower rate, but the real supporters don’t just adjust their rate to the new one; they pay more than that rate — if you have a mechanism so they can do that, such as “Pay what you want.” (Sure: no problem to set a minimum!)

So one of my other benchmarks is how much more than the minimum does the average reader pay? If it’s significant, you know you’re delivering value, especially when you consider a good percentage of them can’t afford to pay more.

Did you have a newsletter since the beginning or when&why did you add it to your online publishing model?

The newsletter was the main idea: I didn’t even have a website for a year! The web was barely ramping up in 1994, and not essential at that time. It has, of course, become essential since.

When I first started the website, there were few tools — no WordPress or such — so each individual page was hand-coded, and uploaded by FTP. It was a pain.

A consultant for the first Email Service Provider (ESP) was an avid reader, so when that company was ready to test its software on a big list, the consultant put us together.

Once there, I pushed for certain things that have become standard for ESPs, such as subscription confirmation (or “double opt-in”), automated bounce processing, easy unsubscribe mechanisms, and throttling (slowing) delivery to the more popular email companies such as Earthlink and AOL so they weren’t overwhelmed with mail from one sender, which could make them unfriendly to newsletters.

Simply, these were “best practices” that the first ESP was happy to implement because they were good ideas.

GROWTH

How did the size of your subscriber list evolve throughout the years? Is it still growing?

It took off like a wildfire. The dominant media of the time (newspapers, magazines, and radio and TV shows) saw this huge force growing in leaps and bounds — the Internet — and “had to” report on it. The most obvious question was, what can you do there?

Since This is True, as news commentary, was fun for reporters to read, a lot of them did read it, enjoyed it, and used it as an example.

My first issue was written as a proof of concept, and was dated 26 June 1994. Then I had to figure out all the tech myself, since there were no newsletter services per se in 1994. Still, I launched online by the end of July.

Since I worked in high tech I had a lot of friends with email, I sent the first issue to 50 of them and said if they liked it, they could subscribe to get more; otherwise ignore it and I won’t send any more.

The first subscription came within minutes. The first foreign subscription came within days. By the end of the month, I had 1,000 subscribers. By the end of the year distribution broke 10,000, which is almost miraculous considering hardly anyone was online in 1994!

New subscriptions continued to roll in: 50-150, and sometimes more, every day, and that went on for years. My list hit 50,000 subscribers by November 1997, 100,000 by January 2000, and 150,000 by its 10th anniversary.

Those didn’t count newspaper circulation, of course: I wasn’t counting on that market, so it was just a nice temporary boost, and more awareness for readers who liked it, and could find it online. More on that in a moment.

Of course growth couldn’t possibly continue at that pace and it slowed down, but a six-figure distribution was terrific, once I figured out how to monetize it. The list finally got below 100,000 at the start of 2010, and is still 5 figures today.

What happened?

Facebook! TRUE was meant to be a quick read that entertained its readers so they could move on with their life in a better mood. Facebook was meant to be addictive, and its audience aren’t “readers,” they’re “users” — just as we call drug addicts.

What do you call it when you spend a lot of time on Facebook? “Doom Scrolling”! Doesn’t sound all that entertaining or fulfilling, does it? But when users spend so much of their time with addiction-driven doom scrolling, they don’t have as much time for reading something more intelligent.

That is slowly turning around and newsletters are seeing a huge resurgence, which is why you are one of several now dedicated to writing about this space!

How did your growth strategy evolve in parallel to your subscriber list growth?

My initial idea was to use press releases to get publicity, but there were so many reporters coming to me that I didn’t have time to do that!

A New York Times columnist called to ask questions about online publishing, and she was so intrigued by what I was doing that she threw away the notes she had so far and made her whole column about This is True.

I then took a clip of that story to a Los Angeles Times feature writer I had met, and he was so unhappy that the New York press had beaten him to the story, he figured he would completely outdo them — and the result was so large and effusive that it was almost embarrassing. Almost. 🙂

Newsweek was still a big deal back then, and saw that and did a bit on TRUE. The CNN Morning News saw it too, and had me on their show. And there were many, many more.

Books were a fine idea, but they were a bit old school, especially the printed ones: I figured that their income would dwindle over time, so I had to figure out a different way to make money.

Which was?

Paid subscriptions. One of the main reasons I wanted my ESP to automate bounce processing was that my first Unix-based distribution system didn’t have it. I had to manually figure out what addresses were bouncing and remove them myself.

It was so horrible and time-consuming that to have the time to do it, I cut distribution down to every other week. I still wrote the column every week because I had newspaper clients, but clearly something needed to change.

Once the new ESP implemented bounce processing, it was a relief — and I realized that it would be pretty easy to create a second list for those who pay to get it, and those readers would get This is True every week.

It was simple, and very successful: there was pent-up demand because readers were only getting half the stories, and they wanted more. Money came pouring in — by mail, since it was still quite expensive to do secure sites and shopping carts.

Pretty soon, one reader put up a page for me on his own shopping cart that would go through my existing credit card processor and the orders came directly to me. It was year three, and I knew I’d make my benchmark: to meet and then beat my NASA salary.

Later, I saw the clear income cycle: every two weeks, there was a new free newsletter, and I’d get a bunch of upgrades, which would level off within a week, and then a new burst with the next free newsletter.

I figured I could nearly double my income by making the free edition weekly again, but how do I have something extra for the paid subscribers? Easy: I cut the free newsletter down to 4-5 stories and often put in teasers about what they missed. The income cycle evened out.

Regarding growth efforts, what would you do differently if you had a chance to start over?

I don’t know that I could have changed much at the time because you never “knew then what you know now.” I just had to figure out what people wanted to buy, and then the harder lesson: how much they’d be willing to pay for it. Not that I was doing badly: in the third year I had matched my NASA salary, so quitting after two worked out perfectly.

By the fourth year I way exceeded that salary, and the sixth year it was almost triple — and I was pretty happy with my old salary.

Looking back, I see I made the classic error: not charging enough. Worse, I waited much too long to increase the rate. Sure, a few would drop off when I raised the rate, but the list was still growing, so many more jumped on board.

Considering you’ve written your newsletter for many years, retention should be especially critical.

What is your retention strategy? How do you nurture long-time subscribers?

I speak directly to readers as people, and respect their intelligence. Sure enough, they like that. I don’t jump through hoops to make them like me or my product, I write what I think, which attracts people who enjoy the intelligence of the writing and agree with my mission: to promote more thinking in the world. When they don’t agree with that mission but want to support it, they come on board.

I think it’s the only way I could be coming up on 30 years writing This is True, and I’m not at all ready to retire. I have pledged to finish at least 35 years if my health continues to be good, and hopefully 40 or even more.

How do you capture evolving needs of your subscribers in time and how do you ensure engagement?

For me, it’s the other way around: because the source material for TRUE is current news stories, the topics are always fresh and relevant. That attracts the readers and, when they understand my mission, they want to support it.

If I mention that I’m tired, for instance (on the side, I’m a volunteer medic in my rural community and can be called out at any time), they tell me to take some time off, and take care of myself! When they’re really honest, they add that they want me to be healthy so I can continue to write TRUE for many more years, because they want it to be there for them to read.

Quite a few of my current Premium (paid) subscribers started paying in 1997, when I launched that edition. Rather than specify a subscription amount, I now let them choose to pay what they want — what it’s worth to them — with a minimum amount specified.

Some have to struggle a bit to pay the minimum amount, which is currently $40/year, and I’m glad they can continue as readers. Those who are doing better pay more — often much more: in the hundreds per year. It’s humbling to realize they value it so much, and I thank them often because they’re making it possible for me to continue working on my mission.

MONETIZATION

What is your revenue coming from your newsletter?

I don’t give revenue numbers, but with thousands of subscribers paying an average that’s much higher than the $40 minimum, it works out well. I still make way above my NASA salary, though I don’t know how much that would be now if I had stayed there!

When and how did you earn your first dollar with your newsletter?

I actually had to look because I couldn’t be sure: it was from the first newspaper to buy TRUE as a column, in January 1995. My first book came out in July 1995, and sold thousands, so that was my main income that year.

How did your monetization strategy evolve over time?

Book sales and newspaper syndication were quite big for the first several years, but today paid subscriptions are more than 90 percent of my income.

E-MAIL SERVICE PROVIDER

Why did you choose AWeber? Pros and cons?

That first ESP that TRUE grew up with was unfortunately sold by its founder, and in my opinion, the new owners didn’t keep innovating as the Internet evolved. I was growing more and more frustrated with them, so I did a lot of research to see where I should move.

AWeber was the result of that research: they were continuing to innovate (and still do today), and I moved there in mid-2010. On the old ISP, my lists resided on a single server; if there was a problem, I had to wait for hardware to be fixed, though thankfully, that didn’t happen often. AWeber has clusters of servers, so if one fails, there are plenty more to take up the slack without any problem. That, of course, is the norm today, but in 2010 AWeber already had years of experience with that architecture.

Plus, they are proactive at “firing clients” who don’t follow good practice, which results in much higher “deliverability” — getting client emails into their clients’ clients’ inboxes. And isn’t that really what their job is? I’ve met the company founder, and he was already well aware of my business, and clearly respected what I had done.

If I really need help, I have his personal email and can write to him, but I usually just go through the regular channels and ask for what I want, since he has teams of customer service reps and developers who know their jobs.

It would take a lot for me to want to move to a different ESP, and as a paid consultant, I’ve helped a number of people get their own lists set up there.

There aren’t many cons. If I had to come up with one, it’s that they’re a fairly complex service because there are so many options, so it may seem daunting for non-techs to wade in without being overwhelmed. They can either use AWeber’s support to get them going or hire a consultant to help. But once up to speed, AWeber’s power allows them to do so much!

All that said, I actually use custom software for my newsletter building and, for the paid edition, distribution (via Socket Labs, in my opinion a better version of SendGrid).

You also launched your newsletter on Substack 6 months ago. What is the strategy behind it?

I was recruited personally by one of Substack’s founders. He liked the idea of having one of the oldest online newsletters in the world on their platform. I said the only way I’d do it is to have a separate special edition for them that had a bit more than my own free edition for a nominal fee, because I am intrigued by their network effect: the Netflix-like “if you like newsletter X, you’ll probably like newsletter Y”.

It’s ramping up slower than I want, but I play long games: I’m willing to be patient, and indeed I’m seeing that sort of subscription coming in fairly regularly now.

Their terms of service actually don’t allow what I do, which is to still pitch the Premium version, which is not in their ecosystem. But he wanted TRUE enough that he waived that term in writing, and has approved what I’m doing. So it’s a nice experiment, and is already bringing in decent revenue considering it’s still quite early.

SYSTEM & PRODUCTIVITY

What is your typical weekly process from creating to promoting a new issue?

TRUE is weekly, so that indeed drives my weekly process.

With the onset of the pandemic, I didn’t hire a new assistant when my employee at the time moved away. Doing the orders myself — mainly subscription upgrades and renewals — both keeps me in more direct touch with the readers than ever, and I saw where the inefficiencies were and designed new processes for the back end of the order flow, which makes it both faster and more accurate.

There are 10-20 orders every day, and with the new workflow, they only take me 10-20 minutes to process. Still, if it started growing very fast again, I’d probably bring in help again.

Late in the week I do story research: finding the source stories from legitimate news sites, which I rewrite into a brief and stylized version, and then add commentary. I have two outside contributors who write some of the content, so I edit those as they come in.

Sometimes I push back to say their comment on the story doesn’t quite hit the mark. One of them likes to do the changes himself, the other is fine if I tweak his taglines.

Story writing and editing is done each Sunday, which takes all day. Once they’re done that evening, I read them out loud to my wife so I can catch problems in flow, or perhaps change story ordering. I also get her feedback, such as “that tagline could be better.”

Once done with that round, the stories go out to a list of volunteer editors, including my wife and my brother. Not all of them look at it every week, but since there are several I almost always get 3-4 replies, and they generally all catch something that the others didn’t.

On Mondays, I put the paid newsletter together: adding photos if they’re both available and add value to the story — I won’t insert an illustration just to have an illustration.

We know that consistency is key to newsletter success. But managing to be consistent since 1994 is an incredible success that we don’t come across very often.

How did you manage this? Which feelings/barriers did you struggle the most and how did you manage not giving up? What was the main motivation for you?

Since I have wanted to be a writer since childhood, it’s simply my job: I’m a writer! I’m very deadline driven: my life is set up to get it done on time each week, and there is usually enough flexibility in my schedule that I can do a volunteer medical rescue without it really impacting me.

I also have enough time to “play” every day, as my wife calls it. She’s a longevity coach who is all about the quality of life.

I have never, ever, wanted to go back to a day job, so that’s enough motivation for me! The better my income is, the more I put into retirement accounts, and I’m not even ready to start drawing from them yet.

Another part of the motivation is I designed my own job, and designed my own publication so that it keeps me mentally stimulated: it’s different every week, and I’m paid to research anything that interests me, and write about it. You can’t get a lot better than that!

NEWSLETTER EXPERIENCE

How do you compare writing a blog vs. writing a newsletter? Pros and cons? How did these evolve in time?

My blog is mainly the “extra commentary” that I write after the stories in my Author’s Notes section. Here is a recent example — the story itself says a lot and gets the point across, but I had spent some time reading about the situation and the school district involved (was it a tiny hick town, or what?), so I wrote more about what I found.

That goes both into the Author’s Notes of the Premium edition, and onto my blog. The free edition gets an intro and link.

The posts are, of course, promoted on social media, too. This particular one brought in more than 1,000 clicks from socials in the first eight hours. That helps get new readers to my site, and likely new subscriptions. Some percentage of those will upgrade to Premium.

Most readers just read; some want to comment too, and the blog gives them a place for that. They also often will share the URL, which brings in new readers too.

What is the biggest difference in newsletter space between the time when you started and now? How did it continue evolving? How do you see the future?

It was very difficult to do newsletters in 1994: there just weren’t services and tools available to help publish them, especially if they had a lot of subscribers.

Even that first ESP I started with couldn’t take me on right away because my list was much larger than they figured, and they had to upgrade their hardware before they could handle it! The only way I could do it is by learning what I needed in Unix for a lot of very manual processes.

For instance, Unix sendmail, server software which does just what its title suggests, would break down with an address list of more than 9,999 subscribers. I literally had to break my list into chunks of 9,995 or so addresses, and send out multiple batches.

My ISP had multiple servers (it was a “shell” service), and I knew how to check the server loads, and how to switch to the server that had the lightest load and bog it down with another 10K sends. Then switch, send more, etc.

Today, there are services and tools and easy shopping carts to handle sales. Not to mention Substack, which does take 10% of your sales, but you get all of their services, which includes the network effect. And if you don’t want to charge readers, it’s free to use.

It’s great for the majority of publishers. If you are like me and think you can go big, and take care of the services and keep that 10% for yourself like me, then there are options like AWeber and WordPress and more.

Newsletters are cool again — people are rebelling against the mindlessness of Facebook and looking for something better. And there IS something better to find when they look.

The challenge, as you alluded to in your questions, is consistency and, in my opinion, quality: if they’re reading, they want good writing — spelling and grammar and punctuation matter. Same with podcasts, consistency is critical, but so is clear and crisp audio, and not a lot of “um, you know, right?” fillers.

But as you know, 95% of newsletters peter out after a few issues, just like most podcasts peter out after a few episodes. So the publishers — and make no mistake, newsletter and podcast publishers are just that, publishers — need a plan to keep it coming week after week. It’s a business!

If they want it to be successful they need a content strategy that’s not just fun to consume, but fun to create, or it’ll become worse than a day job.

How did writing This is True newsletter contribute to your life professionally and personally?

My identity is “writer,” so it’s critical to my life. I figured out a long time ago that writers don’t necessarily make much money, but publishers sure can, and it’s even better if you’re both. The Internet is the most powerful printing press ever invented, and I figured that out in 1994.

I understood in a flash of insight that I didn’t need a newspaper to publish my column: I could reach my readers directly online, and it has worked for 29 years now, with no end in sight.

My readers are fantastic, and they support me and want me to succeed. They understand that if I don’t make money at it, I’ll do something else. I’ve met many who have traveled to my area from as far away as Australia.

When you think about your experience as a newsletter creator during all these years, what are the biggest A-HA moments for you? What are the biggest mistakes and learnings?

My biggest a-ha was being able to put my mission into words. It took a while to fully understand it and boil it down to simple words.

It doesn’t mean I have to be boring about it: I can preach the value of thinking in a very entertaining and thought-provoking way. And it attracts a segment of the population that wants things to be better in the same way, and if they’re entertained too, all the better: they’ll support it if you do it well.

I still get new subscribers every day, and new upgrades every week. Unfortunately, one of the problems with being a 30-year-old newsletter is, it’s no longer a surprise to get a message that says, “I know Bill loved This is True for a long time, but I want you to know he died last week….” or similar.

Many, many, many of them, especially in recent years. Sometimes I expect it, because those readers feel like I’m a friend and they tell me when they’re struggling with cancer, or had a stroke, or whatever.

Some of those letters add that as their loved ones were on their deathbeds, the family would print out their This is True newsletter and read it to them — and that’s when they got the most reaction from their spouse or father or grandmother: they smiled at a tagline! They rolled their eyes over something stupid.

That’s when you know you’re really reaching your audience, even if it’s sad to know you’ll never get a note from them again.

FUTURE

What is next on your newsletter journey?

I’m always thinking of ways to promote my work. Mass media isn’t interested in writing about newsletters or podcasts (there are millions, even if 90% only published a few times).

But all in all, the formula I came up with works, and my readers continue to support me even in the face of Facebook. I love luring people from Facebook to find something better to read!

RECOMMENDATIONS

What would it be if you had the right to give one piece of advice to aspiring newsletter creators?

It’s already been said: the consistency, the quality, the niche. Even I had to work my day job in parallel for two years while I figured out how to make a living from it — and even that changed, so nimble flexibility is key too. And absolutely, an awful lot of luck. (The key for that is to work hard to have more good luck than bad, and use either for all its worth… which is more work. Good luck is more fun!)

Did I say work? Because it is: this is not a part-time job if you want it to be your living. Frankly, it’s probably not 40 hours/week either, so be sure you create something that you love, and will continue to be interested in doing for a long time.

What are your favorite newsletters that you can’t wait for the next issue?

7 Takeaways by Leo Notenboom.

It’s actually a side job for him: his main newsletter is about Windows computing (“AskLeo!”). He’s a tech nerd, but wanted something better than doom-scrolling on Facebook, so he challenged himself to read enough good stuff, including newsletters, to find something to “take away” from that reading to improve his life every single day. And hey, while he’s doing that, why doesn’t he publish them too?

There’s a huge lesson in that approach. He has a passion, and it’s gaining readers.

FINAL WORDS

If you want to succeed in newsletters, subscribe to a lot of newsletters and analyze what they do! One of my readers is a marketing copywriter, one of the best in the business, who worked for a lot of big name marketers.

He subscribes to TRUE because he likes it, but also subscribes to the free edition because he wants to watch how I pitch the upgrade, which is a struggle to keep fresh and evolving so it’s not the same every week. If someone like that can learn by watching how others do it, anyone can!

So, subscribe to a lot of them, and carefully read the ones you like and figure out why you like them. Decide whether you can adapt the ideas you learn to your own newsletter.

Think about what you can learn, because if they’re still doing it after a year, or five, or 20, they’re clearly doing something right.

Also, promote the newsletters you like to your own audience, telling them what you like about it, and send a copy to that publisher without an ask — it’s not a quid pro quo, it’s expressing gratitude that you were able to recommend something good to your readers.

They may not promote you back, but some percentage will, and that’s a great way to grow.